The first dynamic the US should monitor is incumbent Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ Al-Sudani’s electoral performance. The biggest coalition in Iraq’s parliament is the Coordinating Framework, a loosely-allied group of Shi’a parties, some of which are supported by Iran. Iraq’s parliament, led by the Framework, elected current Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ Al-Sudani following the 2021 elections. Now, Al-Sudani’s influence has grown, and he intends to secure a second term while running independently from the Coordinating Framework.

Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq-affiliated Al-Ahad TV coverage claiming Al-Sudani’s affiliations have “shifted” away from the Coordinating Framework. Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq is a militia with political representation in the Coordinating Framework.

Al-Sudani has increased his influence and standing among the Iraqi populace in several ways during his first term. His government spearheaded numerous highly publicized reconstruction efforts, particularly in Baghdad, with official government outlets ensuring that images and videos of these efforts were widely distributed across Iraqi media. Al-Sudani has been an active diplomat, seeking to foster economic cooperation between Iraq and its neighbors [1]. He has also engaged in notably active diplomacy with Washington, including by negotiating the approaching end of the International Coalition’s mission in Iraq [2]. These activities have raised Al-Sudani’s public profile and increased his popularity. Now, as the November elections approach, Al-Sudani is leveraging this influence to build important alliances in hopes of securing a second term. Al-Sudani launched the Reconstruction and Development Coalition on 20 May [3]. This coalition consists of several parties, including some currently participating in the Coordinating Framework: Al-Sudani’s own party, the Al-Furatayn Movement; the Bilad Summer Gathering, led by Labor Minister Ahmed Al-Asadi; former Prime Minister Ayad Allawi’s National Coalition; the Karbala Innovation Alliance led by Karbala Governor Nassif Al-Khattabi; and Popular Mobilization Commission Chairman Falih Al-Fayyadh’s National Contract Party [4].

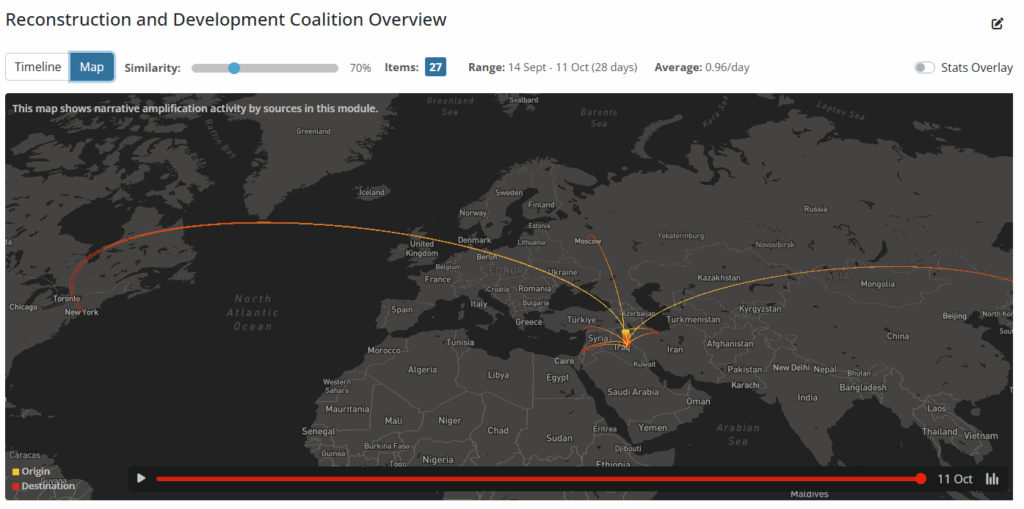

Narrative amplification of discussions of Prime Minister Al-Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development Coalition.

Al-Sudani’s growing profile during his term appears to have coincided with his increasing independence from the Coordinating Framework parties who elected him. In November 2022, at the beginning of Al-Sudani’s tenure, Qais Al-Khazali (Secretary-General of the Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq militia, which has a political party within the Coordinating Framework) famously described Al-Sudani’s anticipated role as simply a “general manager” for the Coordinating Framework [5]. Now, likely due to Al-Sudani’s increasing independence, the Coordinating Framework opposes Al-Sudani securing a second term. Former Prime Minister and State of Law Coalition leader Nouri Al-Maliki, a leader within the Coordinating Framework and initially perceived as close to Al-Sudani, has opposed Al-Sudani’s reelection with particular zeal. On 21 September, an Al-Maliki spokesperson reportedly stated the coalition opposes Al-Sudani serving another term, and accused Al-Sudani’s administration of withholding government services to pressure State of Law Coalition members to ally with him for the upcoming elections [6]. Maliki previously used the Commission to sideline opponents in previous elections [7]. The Coordinating Framework writ large has also sought to hurt Al-Sudani’s chances of a second term; some parties have reportedly circulated rumors that Al-Sudani is a Ba’athist [8].

Edge Theory’s monitoring noted the Coordinating Framework’s opposition to Al-Sudani securing a second term, including Al-Maliki’s reservations.

In short, Al-Sudani is a rising independent political figure that marks a departure, if a modest one, from old, well-known establishment figures like Maliki, and from some of the more hard-line Shi’a Coordinating Framework elements, some of which are allied with Iran. If reelected, Al-Sudani may be able to inch Iraq away from the influence of such forces. However, they will doubtless seek to constrain his ability to do so.

The second dynamic that is critical to monitor is the electoral performance of the political wings of Iran-aligned militias and their allies. Iran’s allies in Iraq’s parliament primarily include the political wings of Iraqi militias historically backed by Iran. Most such parties are currently part of the Coordinating Framework. The electoral performance of Iran’s allies, and how they use the seats they win in the upcoming election, will be particularly important in light of two factors. First, Israel’s degradation of Iran’s Axis of Resistance proxies across the region following Hamas’ 7 October 2023 invasion of Israel. Israel has decimated Hezbollah in Lebanon, and now seeks Hezbollah’s permanent disarmament. Iran’s ally in Syria, Assad, no longer governs in Damascus. The Houthis, while still a significant threat, are contending with strikes from Israel and the US. Iran-aligned militias in Iraq now represent the country’s strongest, most-intact regional proxies, relatively untouched by Israel and the US in the wake of 7 October. Second - US efforts to constrain Iran-backed militias. A bill known as the “Popular Mobilization Forces Authority Law,” proposed on 12 March, would have fully integrated the PMF militias, including those aligned with Iran, into the Iraqi state [9]. The Iraqi government withdrew the law in late August, with some lawmakers claiming the bill was withdrawn under “foreign pressure” [10]. In addition, on 17 September, the US designated four prominent Iran-backed Iraqi militias, Harakat Al-Nujaba, Kata’ib Sayyid Al-Shuhada, Harakat Ansar Allah Al-Awfiya, and Kata’ib Al-Imam Ali, as foreign terrorist organizations [11]. Influence in Iraq’s parliament, and the ability to shape the formation of the next government, is critical for Iran-aligned militias to protect their (and Iran’s) interests in Iraq.

EdgeTheory AI overview of Iranian state-owned Al-Alam News Network’s 17 September coverage of US sanctions on Harakat Al-Nujaba.

All parties running in Iraq’s November elections, including Iran’s parliamentary allies, will seek to win the most seats out of the country’s 329 - seat parliament for two reasons. First, a large share of seats will allow them significant leverage while voting on future legislation. Second, it gives them the strongest leverage in negotiations to form the “largest block” (the absolute majority of the total number of seats, or 165 seats). 165 is the number of votes needed to do most of the work of forming the government. An absolute majority elects the speaker of parliament. A two-thirds majority selects the president (largely a ceremonial position). The president then tasks the largest block with the formation of the Council of Ministers, headed by a Prime Minister-designate. An absolute majority of the parliament then votes to confirm the individual ministers (including the Prime Minister) and the ministerial program. In essence, the largest block leads government formation [12].

In previous governments, Iran’s parliamentary allies have used these rules to their advantage by either negotiating to become part of the largest block, or by seeking to prevent their rivals from forming the largest block. In the 2018 election, Iran-friendly parties - most notably the Fatah Alliance (led by Badr Organization leader Hadi Al-Ameri, who fought on Iran’s side during the Iran-Iraq war) won 48 seats, while the frequent rival of Iran-aligned parties, nationalist Shi’a cleric Muqtada Al-Sadr’s Saairoun coalition, won the most seats (58) [13]. While Saairoun won the most seats and initially formed the largest block, Al-Fatah and its allies (notably including Al-Maliki’s coalition) essentially out-manouvered Al-Sadr by claiming they, rather than he, had attained the largest block. Ultimately, a compromise prime ministerial candidate largely viewed as weak and acceptable to Iran - Adel Abdul Mahdi - was elected to lead the government.

In the 2021 parliamentary election, Iran-friendly parties won drastically fewer seats (with Al-Fatah earning only 17 compared to its previous 48). This decline in seats likely reflected the public’s dwindling satisfaction with such parties, particularly in the wake of the 2019 October Revolution Movement (a widespread popular protest movement that condemned Iranian interference in Iraq and ultimately ousted Al-Mahdi). Still, Iran’s parliamentary allies followed their previous playbook, forming a pragmatic alliance with other coalitions (again including Al-Maliki) that eventually became the Coordinating Framework, and contesting the elections’ validity in court. Ultimately, the Coordinating Framework successfully prevented Al-Sadr’s coalition from forming the largest block and spearheading the government’s formation. Instead, all 73 Sadrist Movement MPs resigned from parliament in June 2022 at Al-Sadr’s behest, reflecting his frustration with nearly a year of negotiating gridlock. New MPs were sworn in in their place, increasing the Coordinating Framework’s seat numbers. Al-Sadr’s followers then breached the Green Zone, first in July, and then in August, following Al-Sadr’s dramatic 29 August announcement of his “retirement” from politics [14]. In the end, the Coordinating Framework led the government’s formation on 27 October 2022, without the Sadrist Movement, and elected Al-Sudani to his first term as prime minister.

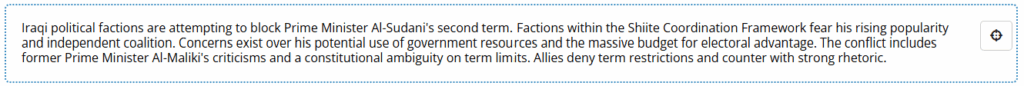

If recent trends continue, Iran-backed parties are unlikely to win a significant number of parliamentary seats on their own. However, we can expect them to maximize their leverage through all means at their disposal - lawsuits and allegations of electoral fraud, and partnering with powerful parliamentary allies including Al-Maliki - to ensure their interests, and Iran’s, are represented when the government is formed. It is worth noting that this year, Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission disqualified a record number of candidates [15]. Notably, this record number of disqualifications comes after Al-Maliki called on the Accountability and Justice Commission (a commission tasked with removing traces of Ba’ath Party ideology from Iraq) and Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission to investigate candidates’ backgrounds to prevent Ba’ath Party supporters from running [16]. Al-Maliki-appears to have used such measures to target his political opponents, including individuals allied with Al-Sudani and even some opponents within the Coordinating Framework [17]. Edge Theory’s monitoring shows these disqualifications have remained a consistent theme in Iraqi media:

The third key dynamic the US must monitor is populist Shi’a cleric Muqtada Al-Sadr’s activities and political rhetoric. The Muqtada Al-Sadr-led Sadrist Movement has played the role of a populist opposition following Sadrist Movement MPs’ June 2022 withdrawal from parliament. The Movement, which Sadr rebranded as the “Shi’a National Movement” in April 2024, has rallied around a range of issues since its withdrawal. Meanwhile, Al-Sadr and online outlets that favor him have vocally criticized the Al-Sudani government and the Coordinating Framework, on issues ranging from the price of the Iraqi dinar, to their interactions with US leaders and diplomats, to their responses to Israel’s actions in Palestine [18].

Footage surfaced by Edge Theory’s monitoring allegedly showing Al-Sadr followers officially announcing a boycott of the November elections in Diwaniyah (Qadisiyyah) Governorate, in response to Al-Sadr’s call.

So far, Al-Sadr and his movement appear poised to continue acting as an unofficial opposition. In March 2025, Sadr announced the Shi’a National Movement would not participate in the upcoming elections and called for his supporters to boycott them. On September 23, Iraqi media reported that Al-Sadr stated he was unable to find a coalition block that aligns with his political goals, which include limiting the use of weapons to the Iraqi state (including an explicit call for “dissolving the militias” and integrating the PMF into the security forces) and combating corruption [19]. For now, it appears Al-Sadr will not support a coalition block in the upcoming elections, while exerting public pressure on participating coalitions to adopt his goals. However, Al-Sadr is notoriously mercurial. Although not a participant in the upcoming elections, he remains a wild card capable of shaping the electoral process and outcome in any number of ways: boycotting, circulating inflammatory rhetoric, publicly supporting or condemning a specific coalition, or using more extreme means such as sit-ins, demonstrations, or violence in the Green Zone.

Edge Theory’s monitoring of outlets covering the Iraqi elections suggest the Coordinating Framework reportedly approached Al-Sadr to mitigate some of the risks of Al-Sadr not fielding a coalition in the upcoming elections (see above). The broader media environment bears this out: from 28-30 September the Coordinating Framework made some attempts to involve Al-Sadr in the political process, potentially to avoid the possibility of his voters supporting their opponents, or to avoid widespread public protest. The Coordinating Framework even reportedly offered to allow Al-Sadr to name the next PM in exchange for his agreement to stay out of the elections [20].

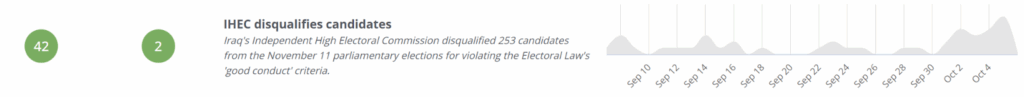

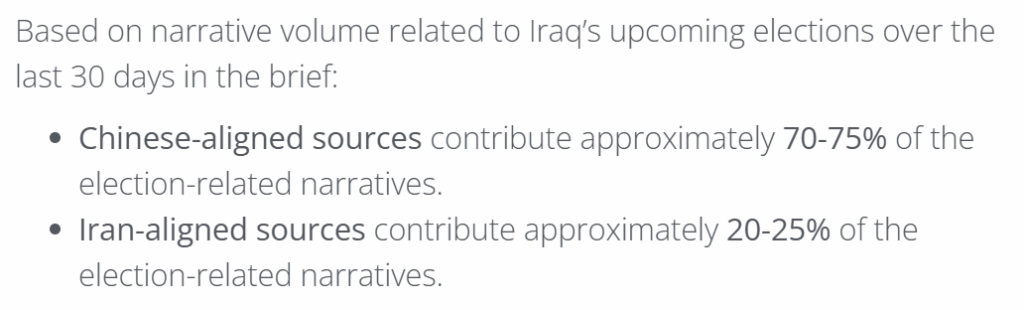

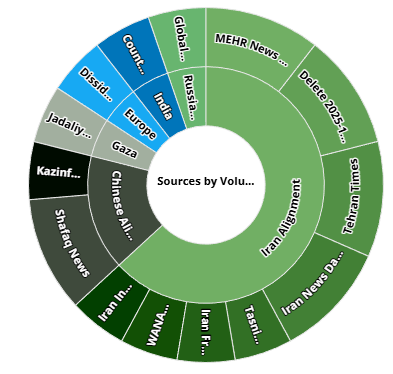

A number of sources supportive of Global Cognitive Adversaries and monitored by Edge Theory engaged in prominent narrative activity over the last 30 days. Of this activity, most coverage of the Iraqi elections came from Shafaq News, which Edge Theory has assessed as aligning with China as it publishes or amplifies content that aligns with themes or perspectives favorable to US adversaries, including China. Meanwhile, Iran-aligned sources (including Iranian state-owned outlets) comprised approximately 20-25% of the Iraqi election coverage within the module. Russian outlets monitored did not directly discuss the Iraqi elections within the 30-day period:

Despite global cognitive adversaries’ coverage of the elections, most narrative themes do not appear to contain language intended to incite or to provoke negative reactions among reading audiences. On a 1-10 scale, with 10 being the highest “likelihood to incite,” the highest-scored article discussing the Iraqi elections received a rating of 3, reflecting that the text highlighted concerns about the election, but stopped short of inciting violence or provoking negative reactions directly:

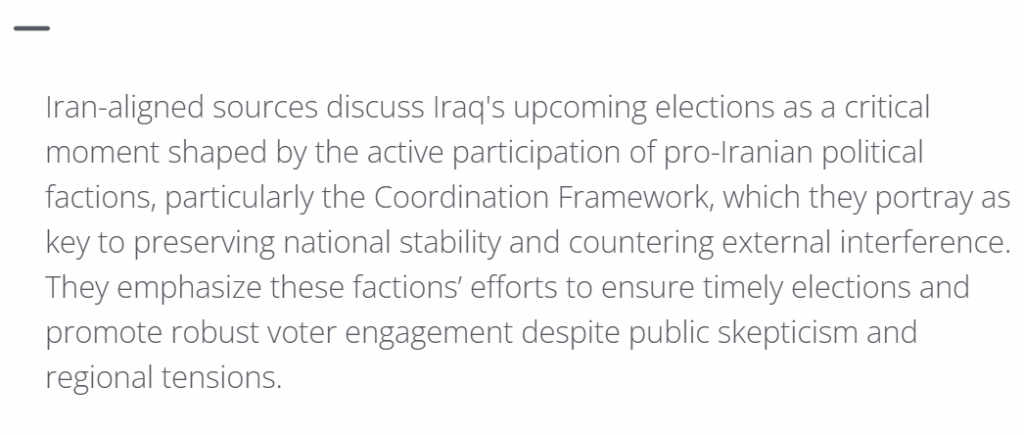

However, Edge Theory’s monitoring did find that Iran-aligned sources portrayed the Coordinating Framework as key to preserving national stability, countering election interference, and holding timely elections with promote robust voter participation:

These emphases could reflect concerns - both among Iran-aligned Coordinating Framework parties, and within Iran - about the potential effects Al-Sadr’s boycott could have on the perceived legitimacy of the elections, and by extension, the next government.

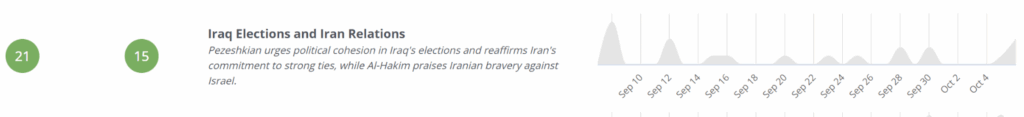

In previous elections and government formation processes, Iran has generally called for unity among Iraq’s Shi’a parties. Notably, on 7 September, National Wisdom Movement leader Ammar Al-Hakim met with Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian in Tehran [21]. The National Wisdom Movement is part of the Coordinating Framework. During the meeting, Pezeshkian reportedly emphasized Islamic unity and Iran-Iraq relations, warning against “divisive agendas” sown by adversaries. Consistent with this theme, Pezeshkian also called for political cohesion “beyond ethnic and sectarian lines” in Iraq’s upcoming election [22]. These narratives were reflected in Edge Theory’s monitoring of Global Cognitive Adversaries’ coverage of Iraq’s elections:

Iran-aligned outlets, including Iranian state-owned outlets, were the primary participants in circulating such narrative themes:

Such commentary may reflect that, as Iran’s regional proxy network has been degraded, and as the US reduces its troop presence in the country, Iran seeks above all else a politically stable Iraq, and hopes to maintain the current status quo, in which its Iraqi proxies are able to continue their operations with minimal disturbance.

The most likely scenario is that neither Al-Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development Coalition, nor the Coordinating Framework, comes out decisively on top. The Coordinating Framework will make deals with other parties to form the largest block and to name a new Prime Minister. While Iran-aligned parties in the Coordinating Framework have suffered from dwindling popularity in the last two federal elections, the Maliki-led State of Law Coalition has garnered significant seat numbers in both (25 seats in 2018, and 33 seats in 2021). Maliki is widely popular in the Shi’a-majority southern provinces, and has an extensive network of political connections and patronage in these regions [23]. In addition, Maliki has signaled (as discussed above) that he strongly opposes Sudani holding a second term. We can therefore expect Maliki to use all means at his disposal to outperform Sudani, and to prevent his reelection. Furthermore, the parties that make up the Coordinating Framework have a proven track record of uniting and blocking their opponents (particularly Al-Sadr) from forming the government - even when they fail to win significant seat numbers. We can expect the Coordinating Framework to similarly unite to isolate Al-Sudani.

The second most likely scenario is that Al-Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development Coalition wins the most seats out of the Shi’a parties running, but still faces steep challenges from the Coordinating Framework in forming a government. In the two most recent parliamentary elections, Al-Sadr’s coalition won the most seats overall by significant margins. However, as mentioned above, Al-Sadr has indicated the Shi’a National Movement will not participate in the upcoming election. This, combined with declining public support of Iran-aligned parties affiliated with militias and the potential advantages of being the incumbent, could make Al-Sudani’s coalition the best-performing Shi’a coalition. Al-Sudani’s tendency to avoid sectarian rhetoric may also mean that Shi’a voters and other demographics, including Sunnis and Kurds, feel comfortable voting for him. However, the Coordinating Framework is still likely to do everything in their power to lead the formation of the next government - even if Al-Sudani’s coalition wins the most seats. Such an outcome could lead to a dangerously protracted government formation similar to that following the 2021 election. The process took over a year, and the government only formed after Al-Sadr’s coalition resigned, and his followers stormed the Green Zone. Alternatively, such an outcome could force Al-Sudani to make a deal with the Coordinating Framework, and to relinquish his aspirations for a second term.