This EdgeTheory Narrative Analysis examines how power is consolidated in Iraq after elections—through post-election negotiations and coordinated narrative control—viewed through the lens of Iranian influence.

The report analyzes how Iran-aligned political actors moved quickly following the recent elections to shape legitimacy—treating the vote as a procedural step, not the decisive moment. As results settled, coordinated post-election narratives shifted attention away from electoral outcomes and toward coalition formation, procedural milestones, and claims of inevitability.

Rather than contesting results directly, these narratives worked to define how government formation would be understood and accepted.

The analysis details how post-election narratives were:

By shaping narratives around inevitability, stability, and consensus, post-election negotiations become the real arena of power.

On 11 November, Iraq held its seventh federal election since 2003.1 Iraq headed into the election with a government dominated by Iran-friendly parties, but tempered by Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ Al-Sudani, who has demonstrated willingness to act independently from Iran-backed militias’ influence.2 The Coordinating Framework (CF), the biggest coalition in the previous parliament, consists of mostly Shi’a parties, some of which are backed by Iran.3 The CF led Iraq’s government formation following the 2021 federal election after sidelining the Sadrist Movement, which won the most seats. (The Movement eventually withdrew from parliament at Shi’a cleric and Sadrist Movement leader Muqtada Al-Sadr’s behest, after over a year of stalled negotiations with the CF). The CF nominated Al-Sudani, and formed the government.4

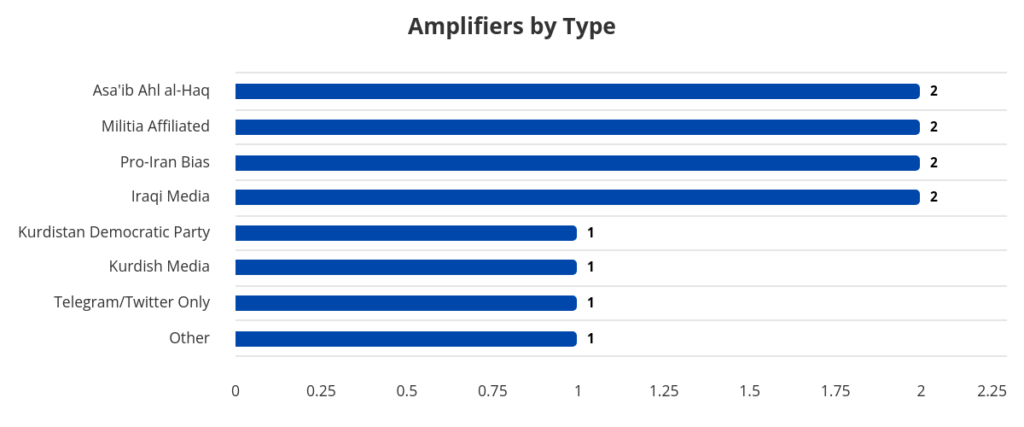

Outlets monitored by EdgeTheory that amplified narratives about the CF between 22-31 December. Militia affiliated sources and pro-Iran sources amplified CF narratives the most. Several Iran-backed militias’ political wings (including Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq’s) are part of the CF, so militia-affiliated and pro-Iranian outlets promote the CF’s electoral achievements. Asa’ib may have been a particularly strong amplifier because the group’s political wing made notable electoral gains.

Despite the CF’s support for Al-Sudani after the 2021 election, powerful CF elements (including those aligned with Iran-backed militias) now oppose him securing a second term.5 He is popular, and has demonstrated openness to working with the US and limiting the militias’ influence. Because of this, the CF parties (including Al-Sudani) ran separately ahead of this year’s 11 November election.6 Al-Sudani’s coalition is the Reconstruction and Development Coalition (RDC).7

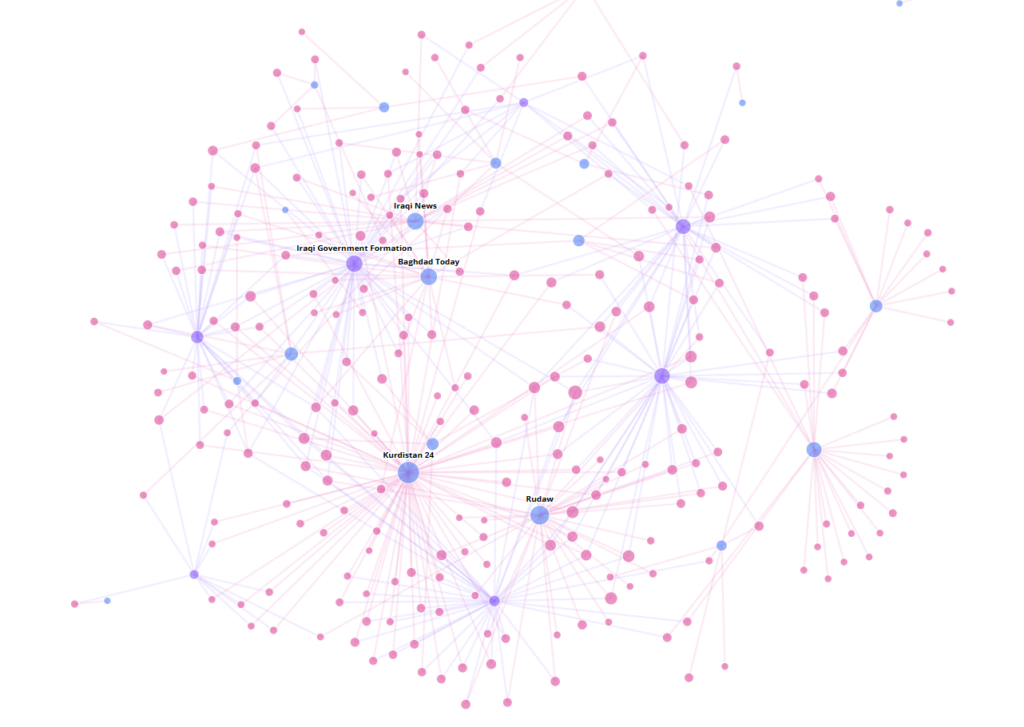

Iraq sources monitored by EdgeTheory covered several themes relating to Iraq’s government formation in the last 30 days. Kurdistan24, Rudaw, Iraqi News, Baghdad Today, and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) media published the highest number of narrative items pertaining to government formation overall. Three out of these five outlets are politicized and linked to Kurdish parties. Kurdistan24 and Rudaw provide pro-Kurdistan Democratic Party coverage. PUK media is the PUK’s official media arm. Iraqi News describes itself as independent, but information on the site’s ownership is not publicly available. Baghdad Today is independent.

Before November’s election, we predicted that the CF parties would wield significant power in forming the next Iraqi government - even if they did not win the most seats. We anticipated that two overlapping scenarios could unfold. First, that neither Al-Sudani’s RDC, nor the CF parties opposing him, would come out decisively on top, but that the CF would build a sizable coalition and play a leading role in forming the government. Second, that Al-Sudani’s RDC would come out decisively on top, but that again, the CF parties would form a coalition, block Al-Sudani from leading government formation and securing a second term, and would themselves lead government formation. Over a month after the election, scenario two appears poised to unfold.

Al-Sudani’s coalition won the most seats in the election. No coalition won enough seats to singlehandedly form the government.

The RDC won the most seats, securing 46 out of parliament’s 329 seats. Former Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki’s State of Law Coalition (a key party in the CF) won the second most, with 29.8 Parties explicitly tied to Iran-backed militias won fewer, but several (like the Sadiqoun Bloc, Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq’s political wing) made considerable electoral gains.9 After each election, Iraq’s constitution requires parliament to follow multiple steps to form the government. Parliament must elect a speaker (traditionally a Sunni), two deputy speakers, and a president (traditionally a Kurd) by an absolute majority of the total number of parliament members.10 On 29 December parliament elected Taqadum Party member Haibat Al-Halbousi as speaker, Sadiqoun member Adnan Fayhan as first deputy speaker, and Kurdistan Democratic Party member Farhad Atrushi as second deputy Speaker.11 Parliament has 30 days from the speaker’s election to elect a president, who is elected by a two-thirds majority of the number of its members.12

EdgeTheory graphic depicting the volume over time of Global Cognitive Aversaries’ coverage of Iraq’s post-election negotiations. Narrative volume likely spiked on 29 December due to Iraq’s first parliament session, when it elected Al-Halbousi, Fayhan, and Atrushi.

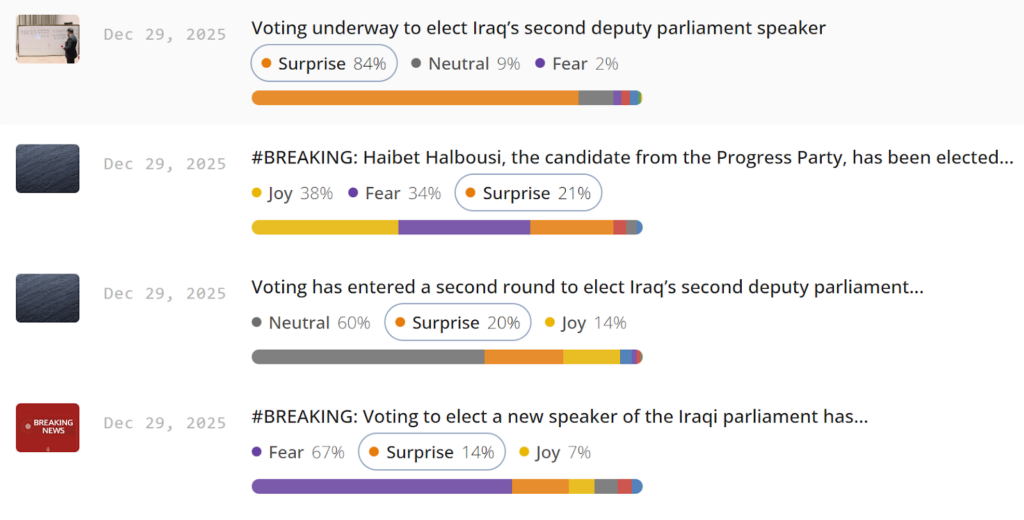

Haibat Al-Halbousi was one of the most widely covered entities within the Iraqi media narrative items EdgeTheory gathered in the last month (top), likely because electing a parliament speaker is the first major constitutionally required step towards forming a government. Among the Iraq sources EdgeTheory monitors, all of the top articles using language indicating surprise on 29 December (the date of the first parliament session) pertained to the speaker or deputy speakers’ election (bottom). This could indicate that the victors surprised domestic observers. In contrast, the bottom item, which announced that vote counting for the speakership was underway, may have scored high on “fear” because intra-Sunni political negotiations to determine the next speaker had been deadlocked for over a month. Meanwhile, the second item (announcing the winner) scored high on “joy,” possibly indicating relief at resolution of the deadlock.

The most critical aspects of government formation - including nominating and confirming the next prime minister and cabinet - hinge on a subsequent step, the formation of the largest block. The president recognizes the coalition that reaches 165 members as the largest block. This block then nominates a prime minister-designate, whom the president charges with assembling a cabinet. An absolute majority of parliament (165 members) then approves or rejects the prime minister-designate and his ministers.13

So, although the RDC won the most seats, the RDC and the runners-up all fell far short of the 165 seats needed to nominate and confirm a prime minister and cabinet. Therefore, the parties must form a coalition to form the next government.

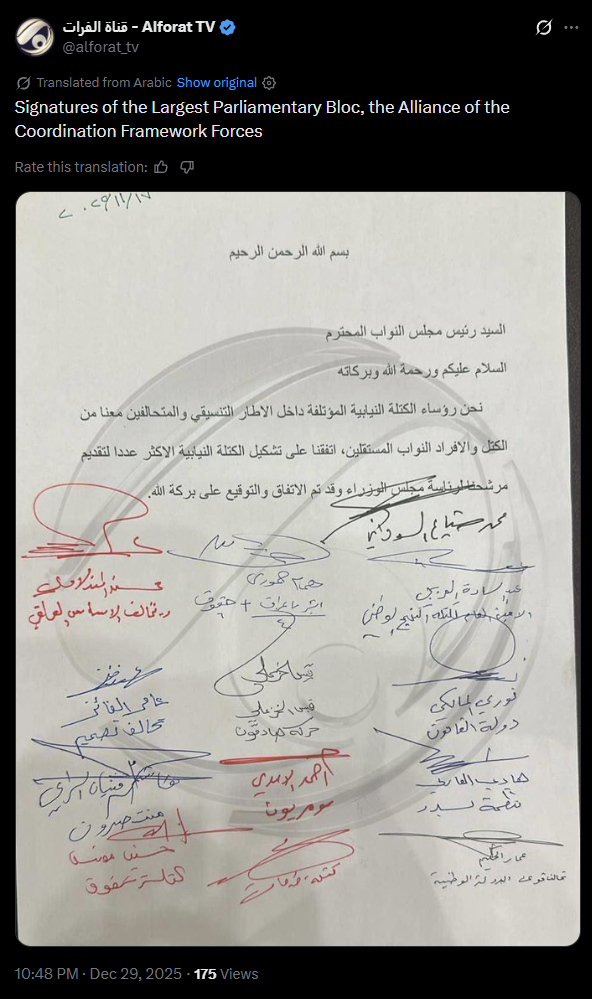

The CF parties collectively have the most seats and therefore the most negotiating leverage. This will benefit the militias and Iran. As of late December, the CF (including Al-Sudani’s RDC) reportedly holds approximately 180 seats, well over the 165 needed to form the largest block and nominate a prime minister.14 Even without Al-Sudani’s 46, the CF still has by far the most seats of any coalition. The CF sought to capitalize on their leverage early on: just days after the election, the coalition announced it constituted the largest block, despite holding only approximately 150 seats at the time.15 Despite some CF elements’ opposition to him holding a second term, Al-Sudani is sticking with the CF: On 18 November, a day after the CF’s “largest block” announcement, Al-Sudani affirmed his party’s participation in the CF, framing it as a “pragmatic” decision.16 On 29 December, in a move not required by the constitution but likely designed to solidify the CF’s claimed “largest block” status, the CF presented a list of signatures of members of the “largest block” to the newly-elected parliament speaker.17 The CF parties’ significant leverage means Iran-friendly parties, and Iran-backed militias, are well positioned to shape the formation of the next government.

The CF parties’ high seat number, and significant negotiating leverage, means that the militias’ (and Iran’s) interests will be well represented in Iraq’s government formation process.

A 29 December X post surfaced by EdgeTheory allegedly showing the “largest block” list and signatures. Multiple CF leaders’ signatures are visible, including Al-Sudani’s, Al-Khazali’s, Al-Ameri’s, and Al-Maliki’s.

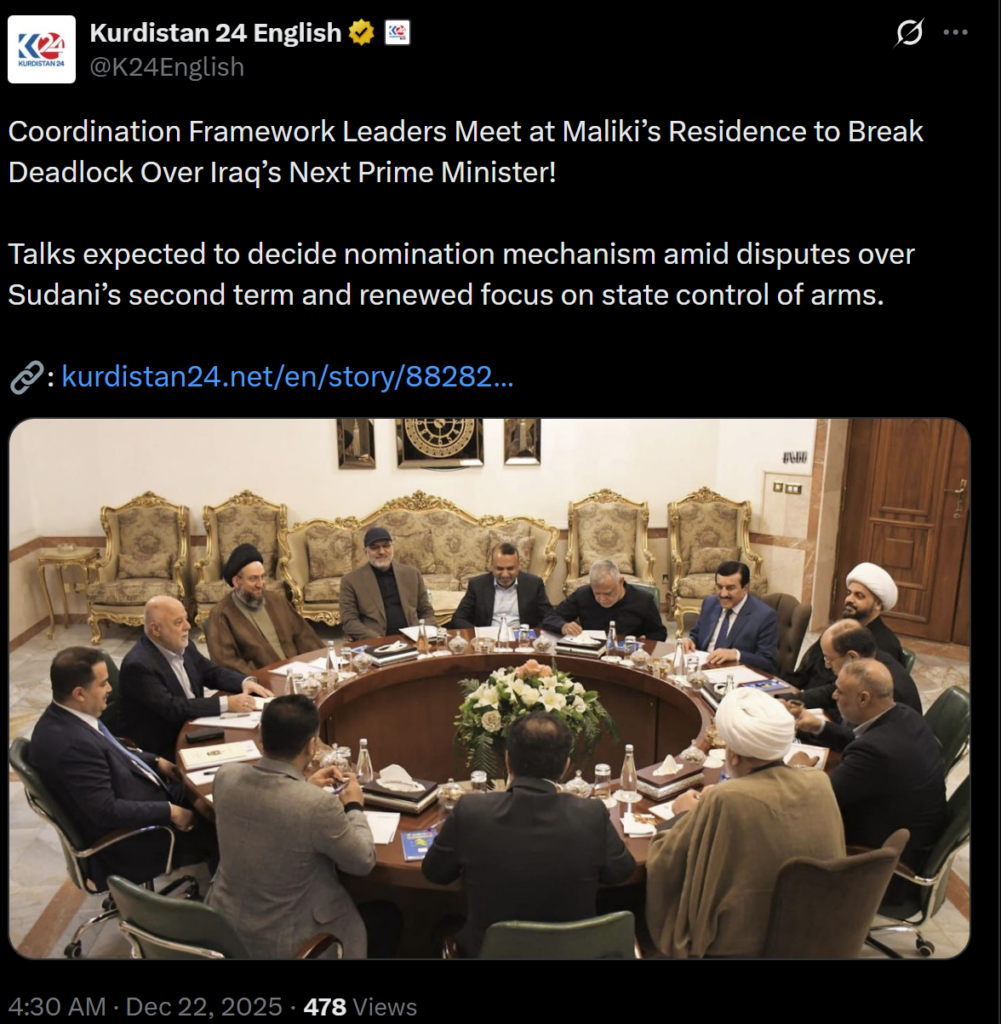

X post surfaced by EdgeTheory describing a 22 December meeting of CF leadership. “State control of arms,” refers to disarmament of Iraq’s extralegal militias, some of which answer to Iran. Prime Minister Al-Sudani is seated at the far left; other CF leaders shown include former Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi, Wisdom Trend leader Ammar Al-Hakim, Kata’ib Sayyid Al-Shuhada leader Abu Alaa Al-Wala’i, Badr Organization leader Hadi Al-Amiri, Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq leader Qais Al-Khazali, and Al-Maliki.

CF parties that oppose Al-Sudani will likely use this leverage to prevent him from securing a second term. Multiple CF elements, particularly the State of Law Coalition, continue to oppose Al-Sudani continuing for another term. State of Law Coalition spokesman Aqil Al-Fatlawi reportedly emphasized on 4 December that Al-Sudani will not serve a second term.18 Among other factors, Al-Fatlawi criticized the Iraqi government’s 17 November designation of Hezbollah and the Ansar Allah (Houthi) Movement as terrorist groups. The designation reportedly angered Iran-backed militias and their political allies.19 Al-Sudani later ordered an investigation into the designation, reportedly in response to militia pressure.20 The designation, combined with Al-Sudani’s previous willingness to buck the CF’s and the militias’ authority, likely reinforced CF resistance to Al-Sudani (in September, under US pressure, Al-Sudani withdrew a bill from parliament that would have integrated the Popular Mobilization Forces militias into the Iraqi government).21 The Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, another CF party, reportedly also opposes Al-Sudani continuing as premier.22 Despite this, Al-Sudani has shown signs he remains interested in another term. During a 22 December CF meeting the RDC reportedly outlined several criteria to end negotiating deadlock over the premiership. The RDC’s statement concluded that if the CF cannot reach a consensus, it should instead use the parties’ “electoral weights,” or seat numbers, to decide the premier.23 This mechanism would clearly favor Al-Sudani.

X post surfaced by EdgeTheory showing Wisdom Trend member Fahad Al-Jubouri (left) claiming the public “will not be shocked” if Al-Sudani is replaced. Al-Jubouri was speaking on Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq-owned Al-Ahad TV’s “Semi Circle” segment.

Although the CF has the most leverage in terms of seat number, they must still balance between Iranian and US interests in nominating a premier. The CF is reportedly considering several candidates, including Al-Sudani, Al-Maliki, National Security Adviser and Badr Organization member Qasim Al-Araji, National Intelligence Service head Hamid Al-Shatri, former Youth and Sports Minister Abdul Hussein Abtan, and Basra Governor Asad Al-Eidani.24 The CF is reportedly seeking a “consensus” candidate who balances the CF and Iran’s interests with the US’, likely in response to US pressure.25 Multiple Iraqi politicians have reportedly confirmed the US has refused to engage with any premier, minister of foreign affairs, defense and interior, intelligence chief, and counterterrorism service head, or army chief of staff with ties to Iran-backed militias.26 The CF is therefore likely seeking a candidate that the US will deem acceptable, but that will also protect - or at a minimum, will not hinder - the CF’s (and the militias’ and Iran’s) interests. The CF’s reported criteria for the next premier supports this.

The CF has reportedly stipulated the next premier should consult the CF before making domestic or foreign policy decisions, should not form his own political party, should have no prior military, security, or judicial background, and must agree to run for his next term as part of the CF.27

EdgeTheory graphic highlighting how Al-Maliki is emphasizing the need for consensus, likely including in relation to the next prime minister. Al-Maliki may seek to portray himself as a consensus choice.

The CF must also balance the interests of its affiliated militias with US demands in the critical months ahead. The 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) states that the Office of Security Cooperation in Iraq, which helps provide weapons and training to Iraq’s security forces, can only receive up to 50% of its allocated funding for 2026 until the Secretary of Defense certifies that Iraq’s government has taken “credible steps” to reduce the capacity of Iran-backed militias operating outside the Iraqi Security Forces, strengthen the prime minister’s role as commander-in-chief, and investigate and hold accountable militia members who act outside of Iraq’s chain of command to attack US personnel.28 On 22 December, the CF issued a statement expressing support for Iran-backed militias’ disarmament.29 Some Iran-backed militias released statements supporting disarmament though several, including one with a political wing participating in the CF, have vocally opposed this.30

EdgeTheory graphic showing the volume of Iraqi media discussing the militias’ disarmament over the last 30 days.

Al-Sudani is unlikely to secure a second term. CF elements’ vocal opposition to Al-Sudani retaining the premiership, Al-Sudani’s several recent moves that have angered the militias, and the CF’s leverage in terms of seat numbers make it unlikely that he will continue as premier. If Al-Sudani does manage to remain in office, the CF will likely ensure that his powers as premier are tightly constrained.

The CF is following a post-election strategy they’ve used for years to steer the outcome of government formation and protect the militias’ and Iran’s interests. The parties that now comprise the CF (usually using different coalition names each election cycle) have deployed a similar strategy following each election since 2018 to protect their interests. These parties have learned that, due to a 2010 Federal Supreme Court ruling stating the largest block can be any post-electoral coalition that collectively constitutes the majority (and does not need to include the party that won the most seats), none of them need to individually perform particularly well with Iraqi voters.31 Instead, they simply need to collectively hold more seats than the winning party, then outmaneuver the winner after the election.

The last three government formation cycles highlight the effectiveness of this strategy. In 2018, the Saairoun Movement, led by Shi’a cleric Muqtada Al-Sadr - a staunch opponent of the CF parties - unexpectedly won a plurality of parliament’s seats.32 Al-Sadr’s coalition won an even larger plurality in the 2021 elections.33 After both, the parties that now constitute the CF banded together and formed a coalition that collectively outnumbered Al-Sadr’s, then incorporated protests, lawsuits, fraud allegations, and deliberate political stalemate as needed to ensure that the CF, rather than the winning party, steered the government’s formation.34 (Note that the Court is influenced by former premier Al-Maliki and Iran-backed militias including the Badr Organization. It has repeatedly issued rulings favoring parties within the CF on critical electoral issues).35 In 2018, this strategy forced Al-Sadr’s coalition to compromise with the CF parties. In 2021, the CF used this strategy to deadlock government formation negotiations until Al-Sadr’s coalition withdrew from parliament entirely. The CF then formed the government without them. This year’s winner, Al-Sudani’s RDC, likely calculates that remaining in the CF fold and compromising is wiser than acting independently and potentially being sidelined by the CF.

The US is correct to pressure the CF to nominate a prime minister that isn’t overtly pro-Iran, and to use the NDAA to reign in Iran-backed militias. But the effectiveness of the CF’s post-electoral strategy means these measures may only scratch the surface. The CF’s strategy means that regardless of which party wins the most seats in each election, it is nearly impossible for Iraq to form a government that would be unacceptable to Iran-backed militias and Iran. Such governments do not always look overtly pro-Iran, but generally ensure that the political, financial, criminal, and judicial networks of influence that Iran-backed militias benefit from are retained and protected. From the prime minister, down through the ministerial and bureaucratic levels, Iran-friendly interests are preserved.

The US is right to push for an independent prime minister, but the US should be wary that a “consensus” or “compromise” prime minister does not mean a government free of Iranian influence.

It can instead mean a prime minister who is weak, lacks his own political base, and is powerless to combat Iranian influence. Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi, who took office in 2018, illustrates this. Iraqi and international media characterized Abdul Mahdi as an independent, compromise candidate.36 However, Abdul Mahdi (like previous premiers) presided over an ever-deepening bureaucratic system of influence in which Iranian interests dominated. This came to a head during Iraq’s 2019 October Revolution Movement, a mass protest movement against a range of issues that included rampant Iranian influence within the Iraqi state. The protesters ultimately ousted Abdul Mahdi, but not before Iranian security forces usurped Iraq’s chain of command entirely by intervening directly to suppress the protests.37 Rather than reflecting an independent Iraqi government, a consensus premier can provide a convenient veneer of sovereignty for a government that is wired to safeguard Iranian interests.

Similarly, the NDAA takes aim at the militias by exerting pressure on the Iraqi government to reduce the capacity of Iran-backed militias not integrated into the security forces, strengthen the prime minister’s command-and-control, and to investigate militias acting outside the chain of command. But, the CF’s post-electoral strategy could mean that the NDAA’s capacity to constrain the militias is limited. Even if all Iraq’s remaining Iran-aligned militias operating outside state authority are “disbanded” and reintegrated into the official government security apparatus (and many are already officially integrated, within the PMF), the CF’s strategy means the government is unlikely to include ministers committed to uprooting Iranian influence within the security forces, even if the ministers do not appear overtly pro-Iran. In a similar vein, even if the prime minister’s command-and-control is strengthened, the CF’s strategy means the confirmation of a prime minister willing to use that control to the detriment of Iran or the militias is unlikely. Finally, the CF’s strategy means that any investigative body formed to examine militias’ extralegal activities would be up against both a parliament dominated by the CF and a prime minister potentially unmotivated to push back against Iran - not to mention a federal court system with a history of making decisions that favor the CF parties.

If the US wants lasting results in rolling back Iranian political influence in Iraq, the US should start preparing now to disrupt the CF’s post-election strategy in future elections. This could include (following the incentive structure of the NDAA), making certain US funds contingent on the repeal of the 2010 court ruling mentioned above. Or, this could mean making funding contingent on passage of an amendment requiring that the prime minister come from within the winning party. Alternatively, just as the US has refused to engage with pro-Iran security ministers, as mentioned above, the US could expand that to include any Federal Supreme Court head or justice with ties to Iran-backed militias. This would rule out the current Federal Supreme Court head, Judge Jassem Mohammed Aboud, who has close ties to Badr Organization leader Hadi Al-Ameri.38 These measures would not end Iranian influence in Iraq, but they would meaningfully broaden US efforts to disrupt Iran and its allies’ political options in the country.