Algorithms. They're unfathomable. Omniscient. Mysterious. All-knowing. Magic? Well… not really.

A large percentage of the population think of algorithms as difficult to understand and ultra technical. They are considered the authority of objective truth, or, in a growing global narrative, something completely untrustworthy.

But when people refer to “the algorithm” — whether they're talking about Facebook's News Feed ranking algorithm or the one Google uses for search, or just “algorithms” in general — do they really know what it means? Judging by how widely the term is used and misused, most likely not.

Simply put, algorithms are instructions for solving a problem or completing a task. Recipes are algorithms, so are math equations. Computer code is based on algorithms. The internet runs on algorithms. The entirety of online searching happens through them. Computer and video games are algorithmic storytelling. Online dating and book-recommendation and travel websites would not function without algorithms. GPS mapping systems get people from point A to point B via algorithms. Artificial intelligence (AI) is all algorithmic. The material people see on social media is brought to them by algorithms. In fact, everything people see and do on the web is a product of algorithms. Every time someone sorts a column in a spreadsheet, algorithms are at play, and most financial transactions today are accomplished by algorithms. On the flipside, hacking and cyberattacks exploit algorithms.

Algorithms are mostly invisible aids, augmenting human lives in increasingly incredible ways. However, sometimes the application of algorithms created with good intentions leads to unintended consequences.

For years, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other platforms have employed the videos you watch, the Facebook posts and people you interact with, the tweets you respond to, your location — to help build a profile of you. These platforms then turn to algorithms to engage the profile of you they've compiled. They can then serve up even more videos, posts, and tweets to interact with, channels to subscribe to, groups to join, and topics to follow. You may not be looking for that content, but it knows how to find you.

This process is swell when it leads users to find harmless content they’re already interested in, and it's great for platforms because users will spend more time on them. However, it ceases to be good for users who get radicalized by harmful content, but it's still good for platforms because those users spend more time on them. It’s their business model, it’s been a very profitable one, and they have no desire to change it — nor are they required to.

For instance, when Facebook introduced their News Feed in 2006 it was just that. The "news" or status updates from most everyone you were connected with. It was like getting the newspaper of everyone you "friended" on the platform: front page stories, sports, arts and culture, opinions - everything. But in 2007 Facebook started using an algorithm that consumed data on the content that a user "Liked" or 'Xed" and then delivered a News Feed that it determined was personalized to the user. As time went on the algorithm grew more sophisticated, so that users saw less and less of the whole newspaper or even the front page in favor of an op-ed or opinion section filled with content from a specific perspective.

This personalized, algorithm-driven News Feed mainly shows stories and narratives that support a user's view of an issue. So the user no longer sees the "front page" or objective content around all sides of an issue and in turn, unfortunately, many users quit being able to discern between actual news and the editorialized version of events. And it doesn't just happen on social media. The public's inability to differentiate an op-ed from factual news recently caused a New York Times writer to be fired.

It's easy to focus on the dark side of algorithms. It is a subject that sells papers and fires up Congress. It is also a valid and troubling conversation that must be had. But all of that sensationalism can obscure the good that algorithms do.

There is a big difference in how algorithms are used to study and drive user behavior (a la The Social Dilemma) versus how algorithms are used every day by technology companies to turn data into meaning and information.

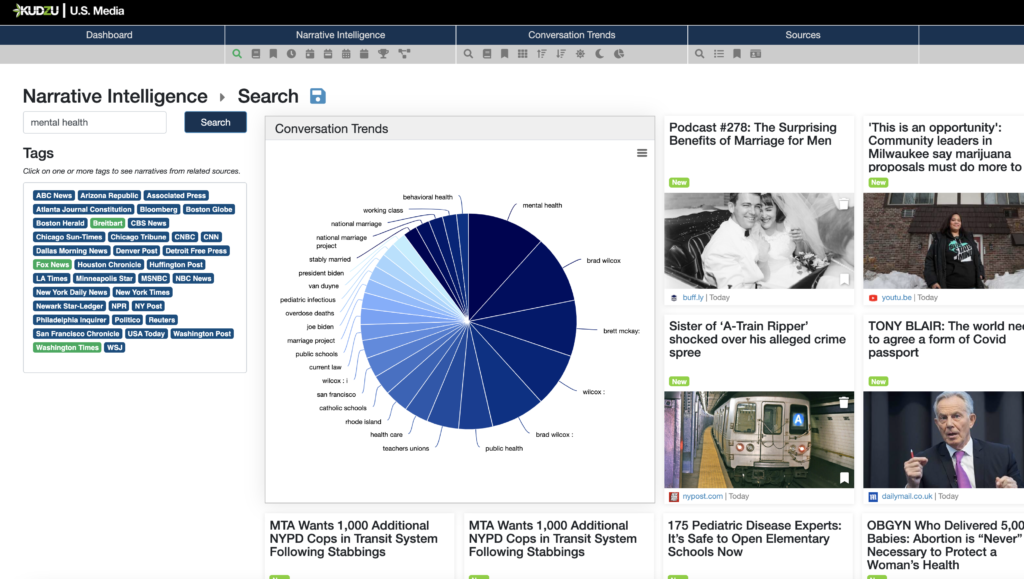

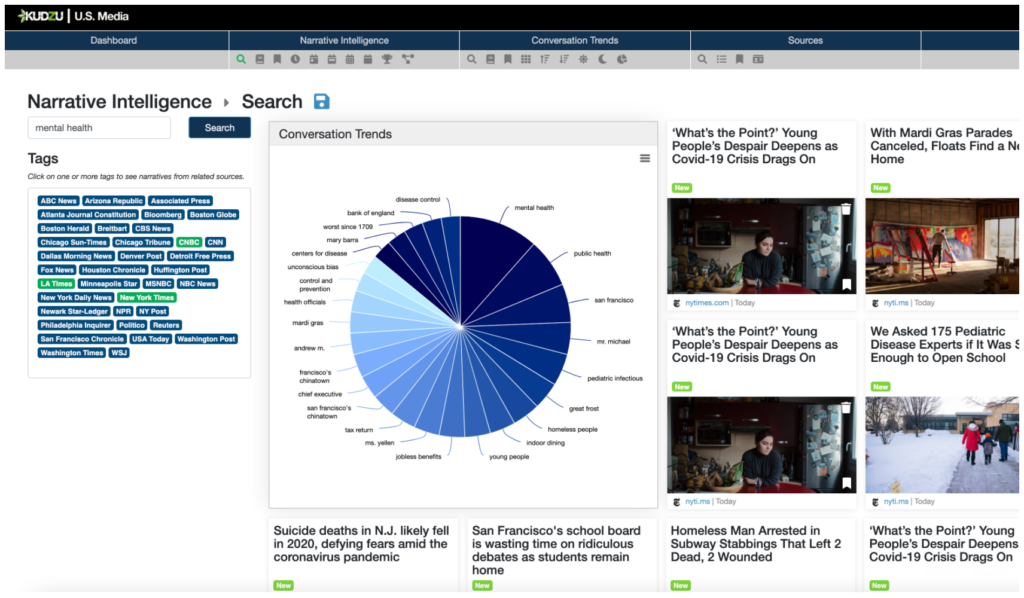

At EdgeTheory, every day we use algorithms to help organizations understand the conversations that shape their world. Every hour, our product Kudzu analyzes a plethora of content sources and subject matter from around the globe and atomizes that information into Narrative Intelligence and Conversation Trends. Kudzu is agnostic to party, perspective, or opinion. There is no bias until a user chooses specific sources or side of a narrative to explore.

For an organization or an individual, conversation is your biggest asset, or it can be a most detrimental liability. There's no way of knowing the extent of a conversation if you're not studying it from all sides. To protect yourself, your business, and your balance sheet you can't afford to be surprised by the narratives that some social algorithms aren't letting you see. You need more than the opinion section. Set up a demo now if you're ready to have access to the unbiased front page.